The Backstory

In July 1938, William Edge lied about his age on documentation in order to enlist in the Army Air Corps. He was sixteen years old. When the Army found about his lie they discharged him and made him re-enlist with his correct age. He was old enough at that point to join now so they re-enlisted him immediately and he continued his training. His re-enlist date was May 1, 1939.

In January 23, 1939, at the age of 20, William married his first wife, Isabelle, 18 years old at the time, just about a month before his unit was sent to Europe. in February of 1939 the 394th Bombardment Group of the 9th Air Force was activated and William was sent to Boreham Air Field in Essex, England. Later that year, on November 24th, William’s wife gave birth to their son, Jackie.

On April 20, 1944, William received his first Purple Heart medal for wounds received in combat. He had a short rest to recover from a wound in his right arm. Less than a month later he was taking part in the 394th Bomb Group’s 33rd mission when his plane was shot down over German occupied France.

The Mission

On May 10, 1944, the 394th Bombardment Group of the 585th Bomb Squadron of the 9th Air Force, also known as the “Bridge Busters”, was preparing to carry out its 33rd mission over occupied territory. The target, a railway station in Creil, France was part of a railway hub being used by the Germans. This bombing run was part of the “Desert Rail” Operation which focused on destroying all the railways leading to the coasts of the North Sea, the English Channel and the Atlantic with the goal of halting the influx of German reinforcements during the months leading up to the Normandy invasion. The railway station at Creil was a critical target for the Allies, as it was in the vicinity of Saint-Leu d’Esserent where the V1-weapons were assembled. The focus of the mission on May 10th was to destroy the train depot, the marshalling yards, and the rotunda.

39 B-26 bombers accompanied by “Pathfinders” were deployed from Boreham Airfield in Essex, England. As a bombardier for the 394th Bomb Group, William Edge was taking part in this mission that was key to helping Allied forces later during the Normandy invasion. William’s Martin B-26 “Marauder” #42-96058 took off at 07:00 and reached the target in Creil at about 10:30. As the bombardier and Navigator, William took over flight of the plane as they neared and was responsible for successfully navigating to the target and dropping the plane’s bomb load. During the successive waves the group dropped nearly 62 tons of bombs on the target. The railway station was destroyed by 70%, more than enough to cripple the use by the Nazi’s. The results of the mission were considered “excellent” by Bomber Command and “a major step forward in the current campaign to hinder the movement of enemy troops and military equipment.”

While the mission was a success for the Allies, unfortunately, there was considerable collateral damage. A passenger train was in the station at the time of the bombing and 74 civilians lost their lives. Over 100 more were injured due to destruction of surrounding neighborhoods.

The Crash

Moments after the bombing run, as the planes were retreating, the German’s retaliated with anti-aircraft defense weapons. William’s plane was struck by “flak” and the pilot, Captain James A. Joy, Co-pilot, 2nd Lt. John O. Johnson, and the Engineer, Staff Sgt. Harold J. Maynard were all injured. The plane was fatally hit and the injured men, along with the rest of the flight crew prepared to bail out. This was every airman’s worst-case scenario coming true.

The aircraft was hit near the front and quickly became out of control. Smoke escaped from the starboard engine, the instruments on board, the radio and the hydraulic system were no longer responding. Communication between the crew members was complicated because the intercom system had been compromised. The men had no choice but to jump when the plane reached 9,000 ft. Once the men bailed out, the B-26 drifted and progressively lost altitude while making wide circles and eventually crashed and exploded in a field 500 meters south-east of the village of Leglantiers around 10:30 am.

As the crash happened in broad daylight, the six downed airmen were immediately sought by both the French Resistance members and the Germans. At the time of the crash the alert was given to the German Military Police of Montdidier and Compiegne and within an hour, Joy, Johnson and Maynard, injured and unable to escape, were captured, most likely near the village of La Neuville-Roy. Staff Sgt. Louis I. Watts (radio-operator), Sgt. William L. Edge (navigator/bombardier) and Pvt. Joseph J. Houlihan (tail gunner) landed near the village of Ravenel. Local French people quickly came to help these three airmen, who would succeed in escaping German searches.

The Resistance

Captain Joy and his copilot Johnson were immediately captured and taken to the German military hospital in Beauvais and then, like the engineer Maynard, taken to German prisoner of war camps.

The exact circumstances of what happened to Watts, Houlihan and Edge immediately after their parachutes touched down are still unknown. From May 10-12th, Joseph Houlihan followed a different route from Louis Watts and William Edge. William and Louis found refuge in the small village of Saint-Just-en-Chaussee, a stronghold of an important detachment of the Resistance. Both were taken in by Jean Crouet, 41 years old and a chemical engineer. Crouet stated that he had taken them over from Doctor Caillard, a celebrated figure of the local Resistance known for his involvement in helping the Allied airmen who fell in the Saint-Just-en-Chaussee area (he helped 87 of them). Aboard his Simca, and with permission to be on the roads due to his profession as a doctor, Doctor Caillard again appeared as the savior in charge of collecting the fugitive airmen and organized their accommodations. Louis Watts and William Edge stayed only one or two nights at Jean Crouet’s before being transferred to another destination.

Georges Jauneau, also known as “Captain Jacques” was told of the men being hidden in Saint-Just-en-Chaussee. Jauneau was a member of the General F.F.I Staff in the Oise. In May 1944, he was about to assume command of the FFI [French Forces of the Interior] and FTP [Franc Tireurs et Partisans] troops in the Centre-Nord sector of the Oise (about 2,000 men). Georges Jauneau also lived in Saint-Just-en-Chaussee where the FTP detachment “Jacques Bonhomme” was established (about 200 men). It was under his responsibility that the three airmen were directed to an escape network. On May 12th, the three airmen were led by his right hand man, Marc Cuny, to the village of Froissy. Marc Cuny, a refractaire, was a very active member of the resistance and was also sought by the Gestapo. He actively participated in numerous attacks with the “Jacques Bonhomme” detachment (sabotage of locomotives, railways, transport of arms and clandestine newspapers, attacks of convoys etc…). Always a volunteer for dangerous missions, he moved Allied airmen gathered in the region, not hesitating if necessary to crash the German roadblocks. On several occasions, he was responsible for the transport of Louis Watts, Joseph Houlihan and William Edge.

After just a few days in Saint Just, Marc Cuny brought the airmen to the town of Froissy. Eugene Ropital and Jean Boisselin both joined the Resistance in November, 1943. They both belonged to a group called “Jacques Bonhomme” which was centered in Saint Just. This group was led by Jean Louvet. Both Ropital and Boisselin volunteered to hide the airmen for three weeks. They would give them a certain sense of stability after the two hectic days they had just passed since the crash of their aircraft.

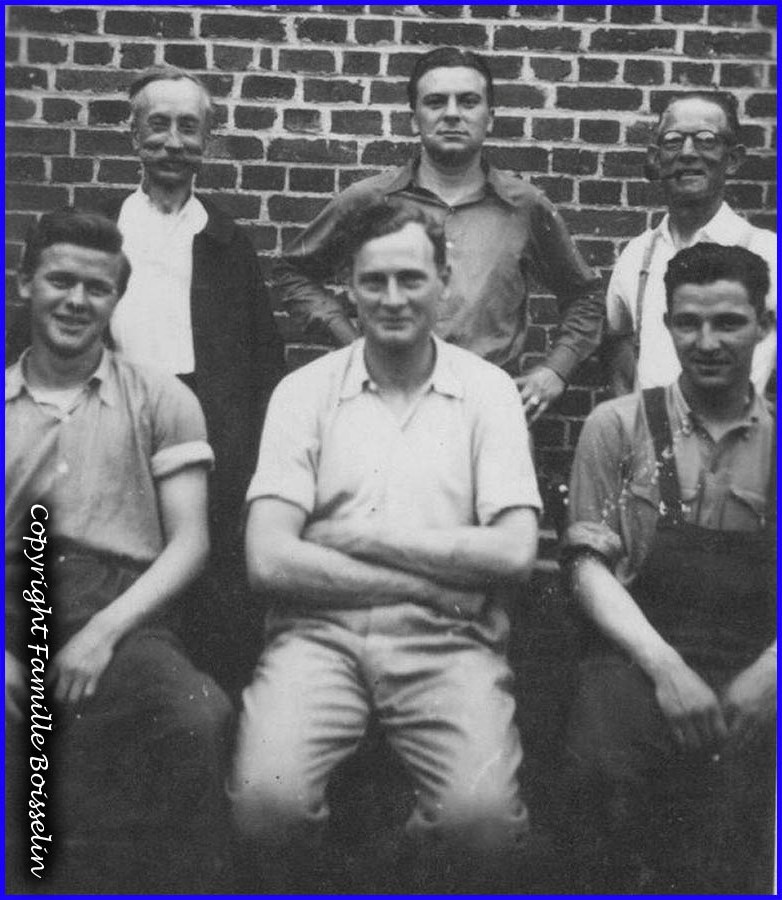

Louis Watts and Joseph Houlihan were cared for by Juliette and Eugene Ropital. Aged 56, Eugene was a saddler and had three children, Rene, Suzanne and Andree. At the same time, William Edge was entrusted to Marguerite and Jean Boisselin. Boisselin, also aged 56, ran a small general store from his home and also had three children: Suzanne, (married and not living at home) Huguette (age 19) and Yvette (age 15). The Ropital and Boisselin families did the best they could to make the airmen as comfortable as possible. We know that strong bonds sprang up during their stay with the families, immortalized by a series of photos taken in Jean Boisselin’s courtyard.

2nd row : Eugene Ropital, An unknown member of the Resistance, Jean Boisselin

From left to right : Lucien Bertin, Joseph Houlihan, Yvonne Fossier, Louis Watts, Suzanne Lequien, William Edge.

After 21 days together, Louis Watts, Joseph Houlihan and William Edge had to hurriedly leave their respective families. On June 3rd , the Germans invaded the village and proceeded to search houses in search of the airmen. Marc Cuny urgently returned to recover them and drove them back to Saint-Just-en-Chaussee.

Although the three airmen were no longer under his responsibility, Jean Boisselin continued to keep abreast of their journeys during the weeks following their departure. He would also pursue the fight by participating in the recovery of food cards for the benefit of the refractories. Eugene Ropital would again be by his side when the time came for the violent battle for the Liberation of Froissy. Shortly afterwards, Eugene Ropital was appointed President of the Local Liberation Committee of Froissy.

Louis Watts, Joseph Houlihan and William Edge were taken to the home of Yvonne Fossier. Yvonne was 26, separated, and had an 18 month old baby at the time. She lived at Rue de Paris in Saint Just-en-Chaussee. Yvonne Fossier was in contact with the members of the “Jacques Bonhomme” detachment. She had previously taken in four other American airmen in January for a few days. Her new boyfriend, Paul Begue helped her then and was going to help again. Yvonne could also count on her neighbor and friend Suzanne Lequien. At that time, a young resistance fighter that was sought by the Germans was also hiding with her; Lucien Bertin. Louis Watts and Joseph Houlihan stayed for a week at her home. It was difficult to keep three airmen together without drawing unwanted attention so the decision was made to split up the crew mates. It is thought that Houlihan and Watts stayed together because Houlihan, being the youngest of the crew, was quite scared. Watts, much older than Edge and Houlihan, was a comfort to him so the men were kept together. This was the last time Watts, Houlihan, and Edge ever saw each other. Marc Cuny then brought Watts and Houlihan to Wavignies. William Edge stayed a full month with Yvonne Fossier until leaving on July 3rd under dire circumstances.

On the morning of July 3rd, the Germans deployed a huge number of soldiers in order to search all houses on Yvonne Fossier’s street, looking for key members of the Resistance. A young man of the organization called “Raoul” had betrayed his group, and the Germans knew exactly where to search.

On this day, a wave of arrests occurred in Saint-Just-en-Chaussee. The raid was on a large scale. Nearly 300 German soldiers encircled the bottom of the Rue de Paris. Marc Cuny and Georges Jauneau managed at the very last moment to escape after a manhunt of several hours. Around 20 Patriots were arrested that day. Most of them were deported to Germany by the last train going from France to Buchenwald. The Café owner died the day he arrived in at the camp. Many others never came back.

The Germans also searched Yvonne’s house. Her boyfriend Paul Begue, himself sought after as a refractaire, had the presence of mind to hide with William Edge in a rabbit hutch. They remained hidden for two hours suspended with “the machine guns of the Boches passing between their legs“. Suzanne Lequien, Yvonne’s friend and neighbor, was aware of the presence of William Edge. Faced with this precarious situation, she decided to help while the Germans crisscrossed the neighbourhood.

In what Georges Jauneau described as an act of “magnificent audacity and courage” she went to Yvonne Fossier’s home and succeeded in extracting William Edge from the mousetrap by hiding him in a baby pram. William climbed down inside the baby pram and a piece of wood was laid on top of him, then Paulette, Yvonne’s daughter who was only a few months old, was placed above. Suzanne Lequien rolled the baby pram down the street to a Gestapo checkpoint. The officer asked her to remove the baby so he could check the pram. She thought they surely would all die. The officer quickly moved around the blankets and then waved her through.

She had done it! She brought William to a safe place, right under the noses of the enemy, to the home of Irene Bourgoin, the sister of Paul Begue. Suspected, Yvonne Fossier was later questioned by the Germans. Her home was thoroughly searched in order to find Paul Begue who in the meantime had managed to escape.

After his perilous escape to the home of Irene Bourgoin, William’s story is temporarily unclear. After just a few days he arrived back at the home of Jean Boisselin in Froissy, on a bicycle and in very bad shape. He said that he had been riding for days and had to ride through the fields and avoid main roads. Unfortunately, he was told he could not stay with the family again, and was taken to Beauvoir by Robert Moulet after only a few hours.

Robert was 25 years old in 1944, and he was a cattle salesman. He was an active member of a resistance network called “Goelette”. As part of his activities, helping airmen took a lot of his time. In May 1944, he met Henri Ménard from Beauvoir. Henri Ménard was a farmer, aged 28, married and father of eight children. When Moulet took Bill to Beauvoir, another airman was already staying with the Menard family: an Australian named Mervyn Fairclough. Mervyn stayed with the family for about 8 weeks, and was considered a member of the family.

Bill arrived in Beauvoir at the same time as Harry Hunter, who had previously been hidden with Watts and Houlihan in Wavignies. Henri could not possibly shelter two more men with his large family. His parents in law – the Le Mouels – accepted to hide them. They also lived in Beauvoir

William and Harry Hunter stayed in Beauvoir with the Menards/Le Mouels family for about two weeks.

The Betrayal

The Traitors

Name: André Cauchemez

Birth date: May 23, 1923

Birth place: Avilly-Saint-Léonard (Oise) Profession: Laborer

André Cauchemez quickly adopts the ideology of the German occupiers and before the age of 19 voluntarily goes to work in Germany in 1942. By September of 1943, he returns to France and becomes an auxiliary agent of the S.D. (Sicherheitsdienst: Intelligence service of the S.S.) in the communes of Creil, then Beauvais. He excels as a traitor, posing as a refractaire or a resistant in order to infiltrate networks before denouncing them. He often takes part in the arrests and interrogations. He is violent, unprincipled and takes advantage of each situation to steal money from those he denounces. He is directly responsible for many deportations to Germany. The arrests of airmen is his main operation.

Name : Paul Villette

Birth date: 16/2/1914

Birth place: Sains-Morainvillers (Oise) Profession : Mechanic

An active member at the service of the enemy, Paul Villette oversees a group of men forming the S.D. auxiliaries of Beauvais. André Cauchemez is a member of that group, as well as three members of the Mesnard family (all with the Milice)

including André Monnier (nephew of Mesnard) and Nicolas Bort. Villette coordinates the operations aimed at stopping all those who supported the Allies. Collaborating with Cauchemez, Villette heads an operation to stop several allied airmen and a group of Russian prisoners who escaped from the building sites of the Todt Organization (engineering and building group of the Nazis).

The Airmen

There are eleven airmen, all hiding in the area: five Australians, two Americans and four Englishmen. Their courses are very diverse, and some have been in France for more than three months. In July, a trap was in preparation. The Gestapo got the word of the many airmen hiding in the area. They decided that the best way to capture them was to infiltrate the Resistance. Two Frenchmen were ready for the job: Cauchemez and Villette.

They worked for the Germans, but posed as members of the resistance. At first, they met many local farmers to collect information. They quickly learned how and where the airmen were hidden. At that point, with the support of the Gestapo, they told everyone that they could find a way to get these airmen back to England by plane (which was impossible at the time). When Robert Moulet met them, he was not immediately convinced, but after a few meetings, he decided that they could be trusted. Robert had just fallen into the trap.

A Three-Day Operation

In the afternoon of July 27th, Robert Moulet instructs his assistant, Guy Brille, to recover four of the airmen. The mayor of Saint-André-Farivillers expresses some doubts about the possibility of evacuating these men by plane, but at the insistence of Moulet, he finally accepts. Guy Brille helps Geoffrey Bennett to get up in the horse-drawn carriage at Vendeuil marsh where an appointment has been made the day before. Robert Moulet is already on board and they proceed to the next stop.

Three airmen are waiting in a grove near the road from Breteuil to Chepoix. The first two are Patrick Hegarty and Philip Dowdeswell, whom André Duboille accompanied to this second meeting point. Henri Menard took charge of the third man he was hiding in his house – Mervyn Fairclough. When Moulet and Brille arrive on the spot, the three airmen climb into the carriage for the next stage of the journey.

This time it is Cauchemez and Villette who are waiting for them at the next rendezvous point located just one kilometer away. At this point the two traitors, Cauchemez and Villette, are about to succeed. They have chosen a remote location in the hamlet of Warmaise between Chepoix and Bonvillers.

At this rendezvous point a car is waiting for them, led by two armed men. Moulet and Brille hand over their “payload” to the false Resistants. The trap closes on the four aviators who, at this very moment, probably think that they are close to freedom….

However, the car is soon stopped by a German roadblock, a part of the plot. The men are arrested and taken to the Agel barracks in Beauvais which is used as a prison. Because they are dressed as civilians, the Gestapo considers them spies. Three days later, they are transferred to Fresnes prison where another story begins.

The next day, July 28th, this time the rendezvous with the false Resistants was fixed in a wood located to the south of Bonvillers on the road leading to Ansauvillers. Bill, Harry Hunter and a British officer named Peter Taylor are taken in a horse-drawn carriage to the rendezvous point. When they approach the woods, the airmen jump from the carriage with Moulet and make the connection with Paul Villette. The same motor vehicle as the day before is there, driven by the same men. The airmen are driven in the direction of Ansauvillers, a nearby village. The same German roadblock awaits them a little further down the road. Peter Taylor, William Edge and Harry Hunter are arrested and taken to the Agel barracks in Beauvais where they suffer the same fate as their companions of misfortune who arrived the day before.

The same operation was organized the next day, with four Australians. Another successful operation for the Germans. In total 11 airmen were arrested in three days. But that is not the end of the story…

Robert Moulet begins to have doubts about Paul Villette and André Cauchemez. Several inconsistencies have occurred. There was no message from London about the safe return of Fairclough that was to be broadcast by the BBC. And the pick-up vehicles for the hand-offs have always come from the opposite direction that would have been the most logical.

At the same time, Cauchemez and Villette do not intend to stop the aviator arrests which have been very lucrative. They plan to meet Moulet on the morning of August 2nd in a cafe in Breteuil, but the two traitors do not show up. Something seems wrong. Moulet receives word that a new rendezvous is planned for the same evening at 10:30 pm in the cemetery at Tartigny. Moulet is now absolutely convinced that Cauchemez and Villette are in the service of the Germans, and he has been outsmarted. He does not go to the meeting and tried to tell his comrades not to go. Moulet was right, the rendezvous at the cemetery is a trap. Cauchemez and Villette are accompanied by German troops. Twenty people were arrested, the three women are released after a few days. All the men, sixteen of them, are deported by train that leaves Compiegne on August 17th, reaching Buchenwald concentration camp on August 22nd. Adding to their misfortune, some say when they arrived at the camp they met several of the airmen they had tried to help. Of the sixteen deportees, ten will not return from Germany.

Post-War Trials

After the Liberation of France, the French Justice system investigated numerous trials aimed at preventing the population from taking justice into their own hands.The judicial inquiry began in the region at the end of 1944. Numerous witnesses were heard, although the fate of the deportees was not yet known. Cauchemez was captured in the spring of 1945. He wanted to get married and discreetly made contact with his parents in order to obtain civil status documents, but this is probably how he was found and arrested!The hearing of the trial took place on the 12th of September 1945 at the Court of Justice in Beauvais. The accused were found guilty on all counts. For Cauchemez, the sentence pronounced was worthy of his horrible misdeeds – the death penalty.At the time of the first trial, Villette was still on the run. In 1946, he was finally arrested and, like his friend Cauchemez, was sentenced to death on the 6th of November, 1946 by the Court of Justice of Amiens.However, the supreme punishment of these two traitors will not be fulfilled. Their sentence was commuted to hard labor in perpetuity by an order of the President of the Republic, and a bit later, to 20 years of imprisonment. Benefitting from remission of sentence, Villette was released in 1960 and Cauchemez a few years earlier. They will never be seen again in the region.

The Camp

After the arrest of William and his comrades, they were immediately taken to Ages Barracks, which was a converted hospital in the north of France, where they remained for just a few days before being transferred to Fresnes Prison in Paris. At the time of William’s arrest he was sent to Fresnes Prison in Paris. Because the men were found hiding with the French Underground, in civilian clothes and without dog tags, the Gestapo considered them “saboteurs and terrorists” and rejected them as POWs under the Geneva Convention.

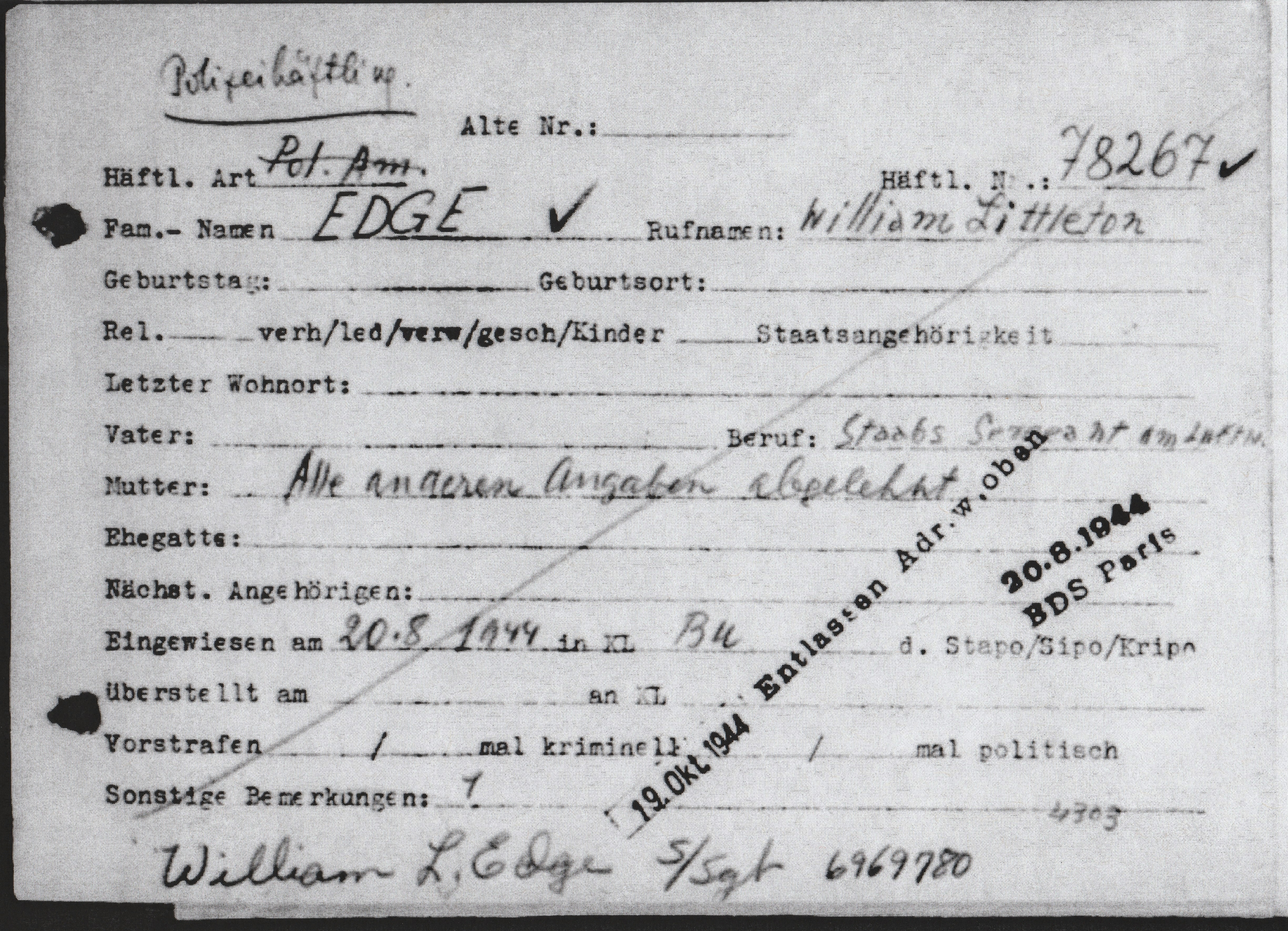

The Gestapo originally listed his nationality, in the upper-left corner, as “Pol. Am.,” signifying him as American. This was later crossed-out and the word “polizeihäftling,” meaning “police prisoner” was written above it. (This apparently was done for all of the Buchenwald airmen – signifying the Nazis’ rejection of their POW rights under the Geneva Convention.)

William was held at Fresnes Prison from August 1st to August 15th. With American troops nearing Paris, he and 167 other allied airmen were marched out of the prison and pushed into cattle cars. 90 men are loaded per boxcar built to hold 8 cattle. They travel for 5 days. No room for sitting, no toilets, just a bucket overflowing with stench and sloshing as the train made it’s way closer to Buchenwald Concentration Camp near Weimar, Germany.

When the train finally stopped, the doors open and there is blinding sunlight, guards screaming in German, barking dogs, whips, rifle butts, barbed wire, pushing, shoving…mayhem. And an imposing brick smokestack. The guards pointed to the smokestack and told the airmen that the only way they’d ever leave that place was through the crematorium chimney. “In through the gate,” they’d say, “and out through the chimney.”

The men are stripped, shaved everywhere, and deloused. Then they are given clothing to wear. Nothing that fits. Some of the mean receive women’s blouses and pants to wear. No one is given shoes or socks. The men are then led to a small pile of rocks. This will be there “home”. They have no shelter. No shade. They live on a small pile of rocks, like pigs or cattle, huddling at night for warmth and a sense of security.

“We are prisoners of war“, they tell the guards. “We should be in a POW camp.” “You are saboteurs caught behind enemy lines“, the Nazis say. “You will die here.” By war’s end, more than 238,000 prisoners – including Jews, Russians, Poles, political prisoners, criminals and homosexuals – would pass through Buchenwald’s front gate with its sign that read, in German: Everyone gets what he deserves. The lucky ones are forced to work in nearby munitions factories until they die of malnutrition or disease. Others are shot. Hanged. Strangled. Or die in medical experiments. The camp’s daily rations: one bowl of grass soup and one piece of bread made with sawdust. The daily ritual: appell – an hours-long head count where the weakest drop from fatigue. “The Germans would knock their brains out with a rifle butt and stack them up at the crematoria,” one of the airmen stated. “That was a common occurrence every day.”

The airmen gain strength from each other. They form a military unit. The 168 Allied airmen at Buchenwald selected New Zealander Phil Lamason, a pilot, as their commanding officer. He was a worthy pick. Lamason maintained the group as a military unit. They marched – even to the latrines. And Lamason steadfastly refused to let any of them work in the Buchenwald munitions factory. For his defiance, he was marched in front of a firing squad – twice. “If I took a step backward, they probably would’ve shot me,” he said. But his answer remained the same: “No, we’re not going to work.” And they never did.

During their stay in the camp William goes from 168 pounds to 89. One of the airman dies of pneumonia. And finally their execution date is set. No one inside these gates can save them now.

They say miracles come from above. In the 168 airmen’s case, it rained down from 30,000 feet as 200 American B-17s bombed Buchenwald’s armament factories and SS barracks. When members of the German Air Force – or Luftwaffe – arrive to inspect the damage, the Americans push a shy, German-speaking waist-gunner out to plead their case. Flier-to-flier. Airman-to-airman. It works. The Luftwaffe officer is surprised to find them there and soon an inquiry is launched. On October, 19, 1944, just four days before their planned execution, the allied airmen were transferred from Buchenwald to the Stalag Luft III POW camp. Some members were forced to march part of the route in the snow. They have survived Buchenwald.

“What was Stalag Luft III like?” one of the airmen was asked. “The Biltmore!” he says. “There was a barracks. There was heat. You got food. I got a Red Cross parcel with GI shoes, pants, shirt and an Eisenhower jacket.” But as the war neared its end, and Allied forces drew near, the Germans moved the men again in February, 1945.

B-26 fighter pilot, William Edge escaped a death sentence at Buchenwald by four days. Yet after the war, the U.S. denied it happened and told the imprisoned airmen to keep quiet. The US was negotiating with the Germans after the war and it was decided that the American people would be less willing to accept negotiations if it was known that US Servicemen had been held in a concentration camp, against the Geneva Convention. “The world isn’t ready to hear it.” they were told. The official U.S. stance was that no American POWs went to Buchenwald.

So the story went untold – except around dinner tables. All of the airmen said that the experience taught them tolerance. One of the men, who was beaten, marched before a firing squad, and starved to near death, puts it this way: “I can’t bring myself to hate. I saw what hate can do.”

The Aftermath

William returned home to the United States in mid-July of 1945. His ordeal with the Germans was over…but that is sadly, not the end of his story.

Sometime after his plane went down in France, his wife, Isabelle was informed that he was killed in action. Consequently, when William returned home to Alabama, his wife had re-married. She and their son, Jackie were living with her new husband in another state. She told William that would be staying with her new husband and that he intended to adopt their son. But she and William had to get divorced first. William fought the divorce for months and finally gave in and granted Isabelle a divorce in an effort to move on with his life.

And move on he did… He met and married Leila in 1946. They had three children, Lynn (in 1947), Deannie (in 1948), and Robert (in 1949). They were married for 50 years when William passed away in 1996.